JBC: Scientists find cellular backup plan for keeping iron levels just right

Iron is essential for cell function, but excess iron can damage cells, so cells have sophisticated molecular mechanisms to sense and adjust iron levels. Disorders of cellular iron metabolism may affect more than a third of the world’s population. In addition disorders like anemia, caused by overall insufficient iron levels, iron deficiency can impair brain function in the young and reduce muscle strength in adults. Iron may be dysregulated at the cellular level in neurological disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, and disordered iron metabolism contributes to congenital conditions such as Friedrich’s ataxia.

Researchers in the nutritional sciences department at the have uncovered a connection in the network of checks and balances underlying cellular iron regulation. was published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry.

When iron levels in mammalian cells are low, iron regulatory proteins, or IRPs, spring into action. IRPs prevent iron that enters cells from being improperly stored, allowing the cell to produce essential iron-containing proteins. When there is excess iron, IRPs are inactive, leading to increased iron storage, lowering potential toxicity and reserving it for when iron availability is reduced. Too much or too little IRP activity can endanger cells.

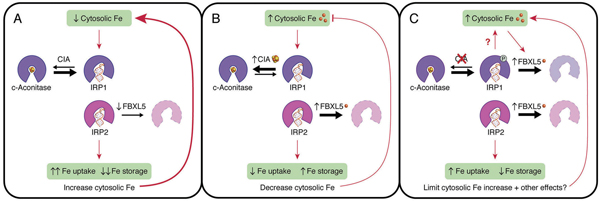

CIA, FBXL5, IRP1 and IRP2 coordinate in control of iron metabolism. Protein degradation and iron-sulfur cluster production can suppress the activity ofiron regulatory proteins, maintaining the correct iron levels in the cell. Courtesy of Caryn Outten, University of South Carolina

CIA, FBXL5, IRP1 and IRP2 coordinate in control of iron metabolism. Protein degradation and iron-sulfur cluster production can suppress the activity ofiron regulatory proteins, maintaining the correct iron levels in the cell. Courtesy of Caryn Outten, University of South Carolina

research group at Wisconsin studies what controls IRP activity. Scientists have long thought the main method by which IRP-1 is inactivated involves essential compounds called iron-sulfur clusters. When there is sufficient iron in the cell, an iron-sulfur cluster is inserted into IRP-1, inactivating it. Thus, the activation or suppression of IRP-1 relates to how much iron is available to produce iron-sulfur clusters.

However, there was some evidence of another method by which IRP-1 could be stopped when it was not needed: namely, that a protein called FBXL5 could add molecular tags to IRP-1 to tell the cell to degrade the protein altogether.

“The idea that IRP1 is also regulated by protein degradation was controversial when it was first discovered by others,” Eisenstein said. “There’s been a belief that IRP-1 was really regulated by this iron-sulfur cluster mechanism, and that the protein degradation mechanism wasn’t so important.”

To test whether this was the case, Eisenstein’s team suppressed the production of iron-sulfur clusters. Even when this production was reduced, IRP-1 activity could still be suppressed. The team confirmed that this was due to the activity of FBXL5. This supported the idea that protein degradation was a backup mechanism that reduced IRP-1 action in cells with high iron.

The results have implications for understanding how iron is sensed, used and regulated in tissues. Different tissues have different levels of oxygen, but the iron-sulfur cluster production system functions best at low oxygen whereas FBXL5 functions best at high oxygen. Therefore, these two systems may trade off taking the lead in controlling IRP-1 in different parts of the body. Because iron-sulfur clusters and FBXL5 play many important roles in cell growth, this balance between these functions could help different types of cells control how they use iron.

“Diseases of iron metabolism caused by diet or by genetic perturbations are major public health issues,” Eisenstein said. “To combat such diseases and develop effective treatments for those afflicted with them, it is essential to understand iron-sensing and iron-regulatory pathways.”

Enjoy reading 91Ó°żâToday?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from 91Ó°żâToday

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Hope for a cure hangs on research

Amid drastic proposed cuts to biomedical research, rare disease families like Hailey Adkisson’s fight for survival and hope. Without funding, science can’t “catch up” to help the patients who need it most.

Before we’ve lost what we can’t rebuild: Hope for prion disease

Sonia Vallabh and Eric Minikel, a husband-and-wife team racing to cure prion disease, helped develop ION717, an antisense oligonucleotide treatment now in clinical trials. Their mission is personal — and just getting started.

Defeating deletions and duplications

Promising therapeutics for chromosome 15 rare neurodevelopmental disorders, including Angelman syndrome, Dup15q syndrome and Prader–Willi syndrome.

Using 'nature’s mistakes' as a window into Lafora disease

After years of heartbreak, Lafora disease families are fueling glycogen storage research breakthroughs, helping develop therapies that may treat not only Lafora but other related neurological disorders.

Cracking cancer’s code through functional connections

A machine learning–derived protein cofunction network is transforming how scientists understand and uncover relationships between proteins in cancer.

Gaze into the proteomics crystal ball

The 15th International Symposium on Proteomics in the Life Sciences symposium will be held August 17–21 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

.jpg?lang=en-US&width=300&height=300&ext=.jpg)