Science on a visa

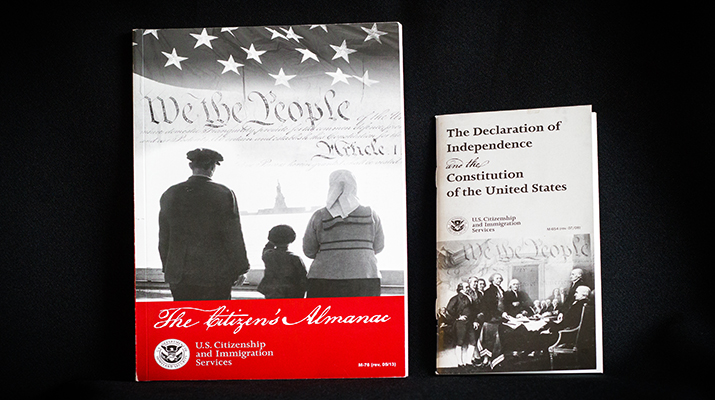

Study guides given to would-be citizens of the U.S. EMILY HUFF

Study guides given to would-be citizens of the U.S. EMILY HUFF

Prologue

It was February 2014, and the sky was a chilled blue. My eyes watered from a vicious cold, but I had to go out. I pulled on a vibrant red jacket. I wanted to be photographed later in the day, and I wanted the jacket color to be symbolic.

In the car with my husband, I tapped on our GPS, entering the address I had received in the mail a few weeks before from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. Neither of us recognized the address, which was somewhere near Baltimore. We soon found ourselves driving through nondescript, sparse suburbia, winding down a road that was surrounded by flat greens and woods.

The GPS directed us to the back of a single-level, gray building that squatted on an asphalt parking lot. A dark glass door with a black steel frame marked the entrance to the building. There was a giant flagpole on the sidewalk in front of the door. An enormous Stars and Stripes, designed to inspire awe, draped from the top of the pole.

Later that February day, I uploaded a photo of myself clutching a small version of the Stars and Stripes against my red jacket. It was official, I told my Facebook friends. I now was an American citizen, 16 years after I first rolled into the U.S. from Canada as a biochemistry graduate student on a Greyhound bus.

The complexity of the visa and immigration process makes those of us who are in it, or who have been through it, skittish. I consider myself to be very lucky to have gotten through the system with a few hiccups. But even with my citizenship and a U.S. passport in hand, I can’t help but feel uneasy revealing how I became a citizen. I don’t want others scrutinizing the steps I took through the visa and immigration maze. I still have flashbacks to sleepless nights spent worrying that an innocent error on my paperwork would get me kicked out of the country.

Back when I was wading through the paperwork, I, like a number of my fellow foreigners, was especially hesitant to voice my concerns about the confusing system. After all, I had decided to stay in the country, so I couldn’t very well complain about what I had to do to stay.

Because most people are hesitant to talk about the issues they face while holding temporary visas or trying to get green cards, I have decided to share parts of my story here. The decisions I made while going through this process were based on my personal circumstances, and every person coming into the U.S. has his or her own unique situation. There is no one-size-fits-all approach to these matters. For this reason, this article should in no way be considered legal advice.

The system and the numbers

From the 1920s to the mid-1960s, admission to the U.S. largely depended upon an immigrant’s country of birth. The quota system during that time favored immigrants from Europe (70 percent of the slots were reserved for the British, Irish and Germans). In 1965, the Hart–Celler Act did away with the national origins quotas and set forth new immigration priorities: facilitating family reunification and bringing in skilled workers from any country.

Since the act passed, according to a recent Pew Research Center , about 59 million immigrants have arrived in the U.S. “For the past half-century, these modern-era immigrants and their descendants have accounted for just over half the nation’s population growth and have reshaped its racial and ethnic composition,” the report said.

Another report, this one released by the National Academies in September and titled “,” noted: “One difference from earlier waves of immigration is the large percentage of highly skilled immigrants now coming to the United States. Over a quarter of the foreign-born now have a college education or more, and they contribute a great deal to the U.S. scientific and technical workforce.”

According to the , 18 percent of the scientists and engineers residing in the United States in 2013 were immigrants. In addition, the NSF found that the life sciences had the highest employment growth among immigrant scientists and engineers from 2003 and 2013, followed by computer and mathematical sciences and social sciences.

To work in the U.S., immigrants must go through the U.S. visa and immigration system. But this is a daunting task. The system “is second in complexity only to the tax code,” said Michael Teitelbaum in his book “Falling Behind: Boom, Bust & the Global Race for Scientific Talent.”

Immigration lawyer Frances Taylor of Baltimore’s Taylor & Ryan law firm wholeheartedly agrees. “It’s absolutely Byzantine. I’ve been working in this field for close to 30 years, and there are still days where I’m learning something new,” says Taylor. “It would be shocking if anybody who is trying to navigate the system could do it easily, without a lot of stress, bother and pain.”

The J-1 visa

Biomedical research relies heavily on non-U.S. citizen postdoctoral fellows. Nearly 60 percent of postdocs in the life sciences in 2008 were temporary residents of the U.S., according to Paula Stephan’s book, “How Economics Shape Science.”

Amita Bansal

Amita Bansal

Fellows who earn their Ph.D.s abroad come into the U.S. on the J-1 visa. The J-1 visa program is designed to give citizens of other countries an experience of American life that they can take back to their home countries. Overseen by the U.S. Department of State, the J-1 visa, with its various categories, allows foreigners to come to the U.S. to “teach, study, conduct research, demonstrate special skills or receive on-the-job training for periods ranging from a few weeks to several years,” according to the department’s website.

Last year, the State Department iss